Greg at a Black Lives Matter protest, June 2020

As an artist, politics can be tricky. There’s a stigma around it in many facets of society, but in the art world – and more specifically the music world –, things feel extra sensitive. Bringing politics into your art can feel divisive when your purpose is to bring people together. Bringing politics into your art can make people angry when your purpose is to create and share good vibes. Artists often try to avoid politics due to the spectre of these and other negativities possibly tainting their work in some way. The reality is, however, that art cannot avoid politics. All art is political, and we as artists have to make a conscious decision about how we will interact with politics and represent our art in its sphere.

The first thing that we must remember is that any attempt at being apolitical is, in itself, political. The art that you create has meaning to it, and any artist will tell you that their art speaks some sort of truth. There is always a personal element to that truth – the art couldn’t have been created without first being filtered through the artist and that artist’s life experiences, after all –; there are truths that those engaging with the art interprets and feels – their very own version of filtration –; there are cultural and historical truths that are inherent in the art; and there are truths that the artist intends their art to represent.

The first two truths mentioned are pretty abstract. They can be open to interpretation and difficult to grasp. If someone studied both Coltrane’s life and music, they would be able to draw connections between what they know historically and what they’re hearing. If that same scholar listened to an obscure jazz record, what concrete truths would they be able to pull from listening? They can only really infer. Whatever truths and life experiences are coming out in the music are abstractions that are being further filtered through the bias of the listener.

Greg and #1 fan Jen Doo at the 2019 Youth Climate Strike

Pat, too! He doesn’t know this exists.

The second two are much more concrete. We, as The Hard Modes, are (1) a band of white musicians (2) playing jazz arrangements (3) of video game music (4) in Charlottesville, VA. Each one of those aspects have histories both separate and intertwined, and those histories are inseparable from their political contexts. Being intentional about how we represent these histories is an act of politics, and therefore, if our intention were to not engage with our art’s history and politics – if our intention is to try and ignore that and be apolitical –, we would still be engaging in politics.

For example: In 2018, we were invited to play for an event called Lambeth Live put on by our local radio station. The Friday night that we played marked the one-year anniversary of the Unite the Right rally in our city where Neo-Nazis, Neo-Confederates, and other white supremacists gathered around a statue of Robert E. Lee that was erected as part of the Lost Cause. This “rally” resulted in the death of Heather Heyer, an activist who was protesting the hate groups, and an immeasurable amount of trauma for our neighbors and city. After Lambeth Live, we were supposed to have another gig downtown, but the city, having expected a recurrence of violence, closed off roads and funneled foot traffic to the area.

While we were on the air, we had a chance to talk about the band and our upcoming performances. At that point we had to make a decision—a decision that was not political or apolitical, but rather, the politics of complacency or the politics of solidarity. Were we to be complacent with white supremacy? Or were we to speak out against it in solidarity with those who are most affected? What would be our truth?

Our message was this: We had a gig after the program and it was cancelled. The echoes of white supremacy had snuffed out the gig. They snuffed out all live art and the enjoyment thereof on what would be an otherwise thriving night in our city. We play Japanese music in the style of Black music and try to honor the histories of each. We play music that embodies what Nazis try to eradicate. We will continue to do so; we will not let them have the last word.

I don’t know how many people were listening that evening or connected with what we had to say. But it doesn’t matter how many were affected; it just matters that we tried to make any effect at all. Igniting a spark in the right place at the right time may light a fire in someone’s heart, and we can’t afford not to strike the match.

Brandon, Greg, Jen, & friends on the local news!

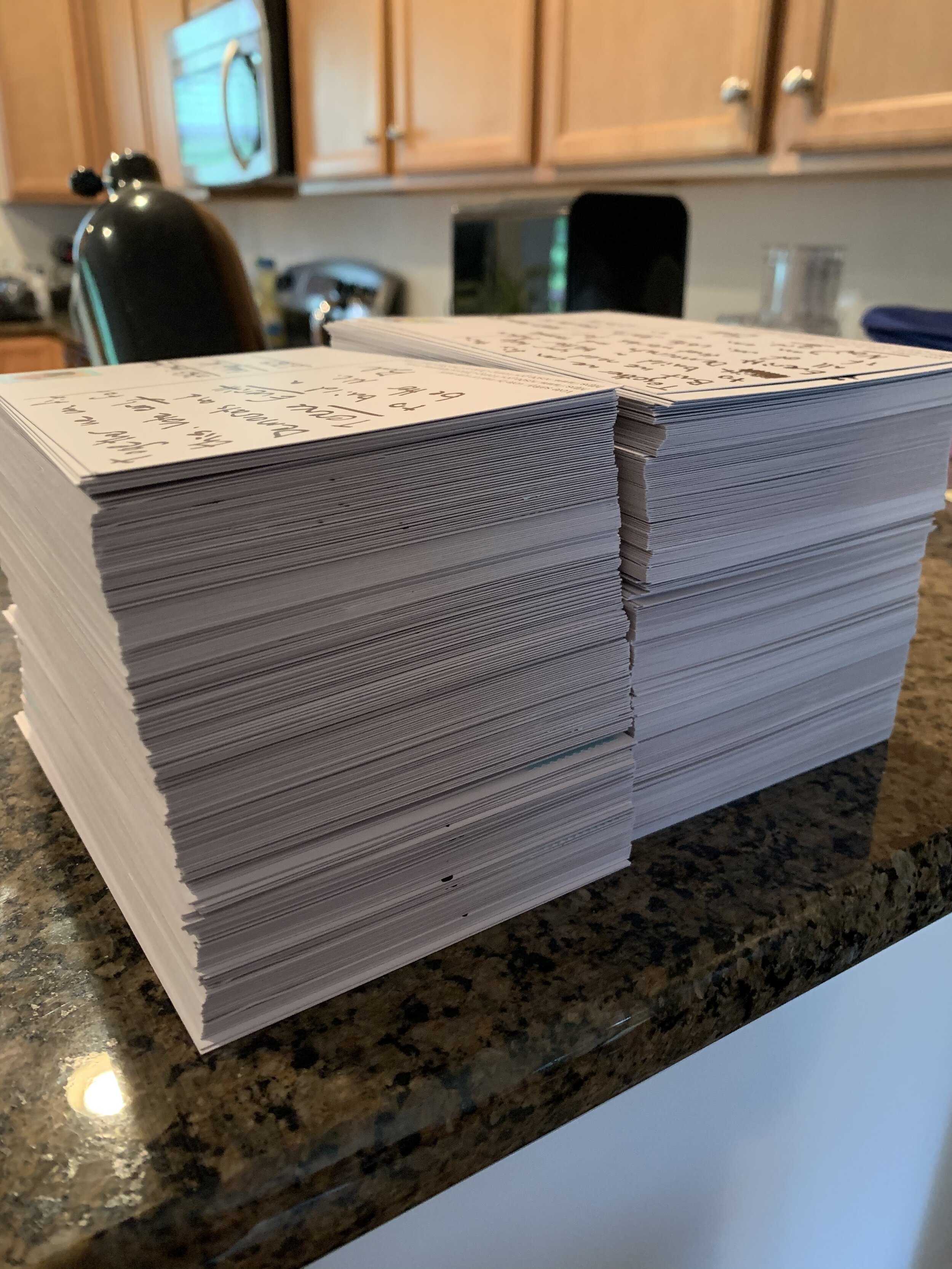

The 600 GOTV cards Brandon wrote @_ @

We have a duty to stand in solidarity. We have that duty as a band that plays Black music. We have that duty as a band that plays Japanese music. And we have that duty as a White band that is working within those traditions.

We have a duty to use our privilege to speak out; to lift up Black people, Black music, Black art, and Black history; to lift up Japanese music, Japanese art, and Japanese history.

We have a duty to lift up the voices of all people of color because they have their own histories of being silenced.

We have a duty to do these things actively. Otherwise, we engage not in the politics of the apolitical, but in the politics of the complacent.

Another point of privilege that our band has is that none of our members play music for a living. We all have comfortable day jobs or are retired. Some musicians feel like they can’t actively speak out because they can’t afford to. They can’t afford the possibility of losing a gig.

Therefore, we have even more duties—we must also speak out against the injustices of our system that muzzle these voices and hold them under the waters of poverty. I have spoken on Twitter about these issues before (e.g., here and here) and I will continue using our platform to speak out.

We can’t be the only ones who do so. We have 169 followers on Twitter. We’re a drop in the bucket in the huge video game music community. We will continue to shout into the void to connect with one or two people periodically and we will do it happily.

But if you’re a leader in this community – or any community – with thousands of followers, you are also called to stand in solidarity with the histories and cultures that you represent.

If you can afford to do so, make the conscious decision to use your power for good. You can actually make a difference. You inspire others with your art, and you can also inspire in other ways. Other artists look up to you. Your listeners look up to you. You’re not, as I said in an aforementioned Twitter thread, a monkey whose job it is to dance for others, nor a mindless sack of meat. People may not come to you for anything other than music, but if they leave because you speak out against injustice, let them leave. If the price of uplifting others and inspiring them to speak their truths, then that in itself is worth losing a few followers.

Remember that standing in solidarity does not mean just telling people to go vote every once in a while. Telling people that when they don’t know what you stand for is empty—it’s complacency since you’re telling people to vote whether or not they stand for justice or injustice. Speaking out and encouraging others to speak out – whether directly or just by virtue of using your platform to inspire – is acting in solidarity.

Being apolitical is an illusion. Your art has a history and you can choose to represent it in one way or the other. Speak its truth and yours. Stand in solidarity. Empower your fanbase. Strike the match.